I had the good fortune and great pleasure of collaborating for many years with Groupe Chronos, founded in 1993 and headed until 2015 by sociologist Bruno Marzloff, an illustrious researcher, author and consultant in the fields of mobility and work transformation.

With Bruno and his colleagues, including Laurence Sellincourt, Léa Marzloff and Julie Rieg, we have developed many initiatives and had long and fascinating conversations, including this article-interview that I’m publishing here, which was posted in 2009 on the Groupe Chronos website (now merged into Auxilia, an associative company part of Groupe SOS, headed by Bertil de Fos).

As Groupe Chronos’ focus is on mobility, this text focuses on the challenges of information design in this particular sector. However, what I consider to be the fundamental principles of information design as a discipline are laid down here.

To quote the closing words of this text: “These principles don’t vary, whatever the field you’re working in: when you’re in finance, information is a difference between one value and another. The challenge when working on information design is to understand how to stage a difference so that it is perceived as relevant by the person who has to use it”.

Information, a transport mode in its own right

“The complexity of mobility exceeds the threshold of our cognitive integration capacities. [Dès lors] network information is no longer an instruction manual for the network, it’s a mode of transport in its own right. As a result, information has to be universal and comprehensible to be accessible, and therefore qualitative.

Giuseppe Attoma Pepe makes these remarks in a short video from the ” 27th Region” series. The service designer’s reading of information processing is brutal: the authority has not taken the measure of the transformations in users’ attitudes to the organization of their mobility. Urban complexity is becoming such that it calls for a radical transformation of information.

Faced with information chaos in the city, individuals learn to develop their own strategies and need to take ownership of the data they use. The director of the Attoma agency postulates that we won’t solve complexity with a single homogeneous piece of information, and that we need to find a new balance between individualized information and collectively comprehensible, “standard” information. In a nutshell, it’s all about empowering users to deal with the “urban mess”. Indeed, Fabien Girardin uses the same expression when he advocates a new syntax for the city.

Informing means providing access to complexity

Look at Paris! – but this is true almost everywhere – let’s face it, the city’s resources are “messy”: information isn’t always where and when it’s needed, and when it is, it’s mostly erratic and ambiguous, even contradictory. There is no coherent, consistent rule throughout the city. There are some things that work at a given moment, but they can’t be generalized, like the bus lane, which is sometimes cyclable and sometimes not. This is counter-intuitive: the user is baffled, in a way trapped from a cognitive point of view, and thus exposed to a certain degree of risk. The Mairie de Paris had launched a call for tenders for the design and testing of a legibility system for the Paris cycle network. A good approach, but we got the feeling that his vision of things remained event-driven, in the spirit of Paris Plage. They don’t yet seem to be in a long-term, structuring logic of use, but in a logic of communication and visibility. We’re not building a system of clarity and responsibility, based on a give-and-take relationship. Want to use your bike in town? You do so at your own risk, and it’s up to you to develop your own strategies, which will remain heuristic, subjective and individual.

In our thinking at the agency, we work on an extremist hypothesis, based on the paradigm that complexity has now passed a threshold of resolution and that we will never return to a naturally viable state, in which systems remained within the reach of our elementary cognitive capacities. So the question is: “How do we live when all perception of simplicity is gone, when continuity doesn’t exist? This seems to us to be the real fundamental question, because all the usage studies we carry out as part of our projects teach us that, from now on, the complexity of mobility exceeds the threshold of our cognitive integration capacities. We are less and less able to treat it effectively and satisfactorily.

Informing means adapting to everyone’s “language

We all tend to mentally construct maps of the territories in which we move; in fact, we do this all the time. These maps are sometimes, indeed very often, wrong in relation to geographical reality, but they are functional to our needs at a given moment, and in this sense they have their degree of effectiveness. We create our maps based on our knowledge, our cognitive models and our cultural models, and it’s quite funny in some of the experiments we’ve carried out, to superimpose a number of them and observe so many differences in “language” in the apprehension and representation of the same territory.

The problem is how to solve this babel. The Babel metaphor seems apt to me: everyone speaks a different language and has a singular cartography of the city. And this is made even more complex by the immaterial infrastructure that objectively exists: for example, the navigation tools offered to users present different interfaces; each universe has its own pricing, etc. What tools do we give users – or not – to deal with these issues?

At Attoma, we are currently developing a methodological approach with a researcher in cognitive psychology, who comes from the world of motor rehabilitation and has spent a long time observing patients undergoing rehabilitation. The idea behind this is that the complexity imposed on us pushes us beyond our cognitive processing capacities and puts us in a constant situation of “rehabilitation”, obliged to develop individual strategies of adaptation and circumvention. Based on this working hypothesis, we are developing usage observation protocols that enable us to observe errors at the level of attachments in order to identify nodes, and understand how to constitute micro-solutions, micro-translation keys.

Is a “homogeneous” information model still possible?

The challenge of information today oscillates between two formulations: Adapting information to each individual and Seeking homogeneous information that everyone can understand. Let’s imagine a cursor between these two poles. In fact, he positions himself according to the system, local contexts, technologies, business models, as well as political and regulatory issues. Today, it’s primarily in the technical aspect that we look for homogeneous information. But information will multiply its forms, both immaterial and material. We’re going to learn to negotiate with objects that don’t look alike, with different syntaxes – and in fact, that’s what’s already happening. We still need to understand where to place the cursor so that information is understood by the greatest number of people. It’s all a question of language: at what point do we stop recognizing it? A further layer of complexity is added: when a language evolves, it becomes something else.

When road signage was created in the United States, at the time of the development of highways, a single organization established common rules for all states. These same principles have been progressively applied, in a relatively stable way, throughout the world, and in the end, we can observe a relative consistency in this system. Imagine, on the other hand, a world in which this didn’t work, and every department, every region, every state had its own road signs. This is to some extent what is happening today in the field of multimodal information. These are fragmented universes that may share identical data formats and IT protocols, but the processes and stakes involved mean that, in the end, not everything is the same. For the user, the problem is certainly not the computer format of the data, but the logical structure and visible aspect of the information presented.

This raises the question of the relevance and chances of success of a global standardization ambition, and we have to accept that we will never have a truly homogeneous macro-system, speaking one language and with one voice. This ambition is perhaps no more than a belief inherited from a positivist paradigm that is now outdated.

Informing means adapting language to different configurations

Even if some individuals manage to play with all available information syntaxes, like “new polyglots”, a majority of them may never leave their own language and even their “dialect”.

That’s not a problem, as long as we stick to a local scale and routine practices, both in terms of mobility patterns and geographical perimeter. But as we move away from this vernacular core, the universal gradually takes over.

The traveler who only takes the plane on an exceptional basis needs to find a scale of information at the airport that would seem completely disproportionate and incongruous in his everyday life.

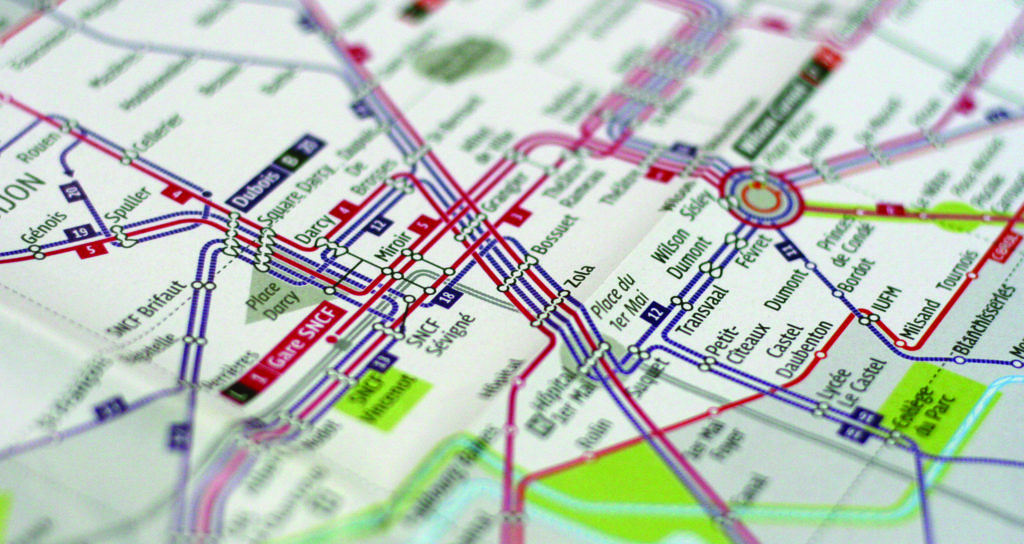

With regard to the projects we carry out at the agency, we regularly ask ourselves questions on this theme. For example, we’re working on a lot of projects involving on-board vehicle information systems, particularly for bus networks. You’d think it’d always be the same. Well, no! Indeed, we’re always wondering what the next stop is, and so on. Of course, there’s always a common syntax that relates to the theme of the journey. But in reality, for a network with a lot of suburban routes, it’s quite different from a network of high-service city lines. Information scenarios are not at all the same, as we have found when developing this type of project for cities such as Paris, Évry, Dijon, Lille, Rennes, Brussels… As part of an on-board information definition project we carried out for the SNCF’s new commuter trains, we noted that each local configuration can be potentially different – hence the difficulty of designing a syntax that is sufficiently articulated and rich to accommodate differences within a framework of coherence and predictability recognizable by the user.

Informing makes a difference

There is information when there is something of the order of difference. For example, in a journey, there is a first place as the point of origin and a second place as the point of destination. Between these places, something varies: it’s time, it’s space. There’s a difference. These principles do not vary, whatever the field of interest: in finance, information is the difference between one value and another. The challenge when working on information design is to understand how to stage a difference so that it is perceived as relevant by the person who needs to use it.